Programming in the Life Sciences #7: theory

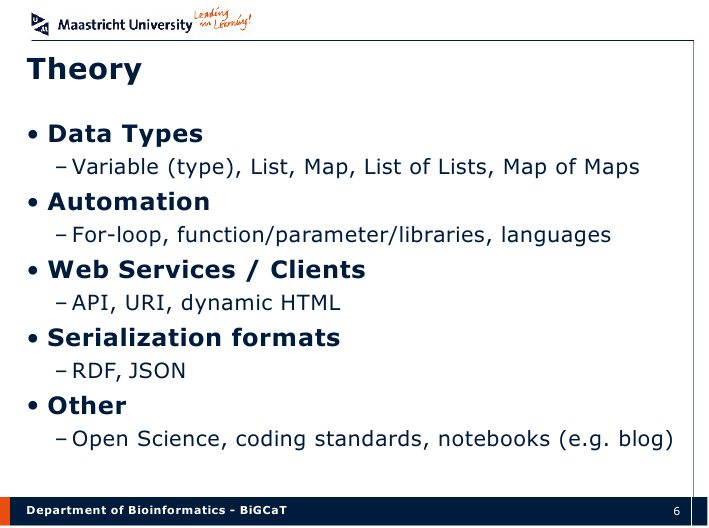

No course, with some good theory. In this six-day course, I plan to cover this computing theory. It’s very practice oriented:

That should give them enough head start to work on something like this. The material will be more extensive, but I’ll give myself a head start, with some initial content.

Introduction

Programming in the Life Sciences is done to solve problems in the life sciences, but only problems that can be solved with pen and paper too. Programming cannot measure metabolites in a cell. For that, you need equipment that gives the things it measured as data as input to the computer.

Instead, the program defines some computation that is done on the computer. For example, noise reduction, DNA/RNA/protein sequence alignment, metabolite identification, etc. But all computation start with input data.

The program tells the computer what it should do, step by step. Get the data from the LC/MS; find peaks; group peaks at the same retention time; match that against a metabolite spectral database; determine the best match; report the best three matches to the user via the screen. Step by step.

The computer consists of input/output devices (to get data; to present results), various kinds of memory (to remember things), and a central processing unit (CPU) that performs the computation steps.

Considering all this, programming is to define what the computer should do, in a (programming) language that the computer understands. Note that I say “the computer understands” rather than “the CPU understands”. The CPU only speaks one language (machine instructions). But we use a higher level programming language, which is much more compact and easier to read/understand. A compiler translate this higher level language into machine instructions (sometimes more compilers).

Data Types

The programming language says do this, do that. It does not know about data. Fortunately, it knows about bit, and bits we can use to store data. That way, we can instruct the CPU to do things like: OK, take the measured LC/MS data, take the MS at retention time 5, then start with the first m/z value, and if that is larger than 10, then… etc. We do not want to hard code the data in our program, so we instruct the CPU to remember it. The computer has various levels of memory that are relevant (ignoring those at a CPU level!): variables stored in the working memory, and data stored on external memory (hard disk, USB disk, LC/MS machine).

Exercise: write a program that counts the sum of all numbers starting with 1 up to 50 without using variables.

Some programming languages have variables types. This variable is a non-integer number, this variable is a text string. This ensures that you cannot sum up “cat” with 5.3. This is called variable typing. Some programming language have hard typing (types are defined in the source code), while others have dynamic typing (the program figures it out when it is compiling), and some even no typing at all (the computer will complain when it runs).

Example basic variable types include: string, integers, floats, and booleans. Strings can be used to remember names; integers are needed for counts and iterations (how many m/z values did I already look at again??), and floats are needed for pretty much all scientific data. A boolean is a yes/no type, or true/false.

Also, variables do not have units. Remember those high school days? “John, six WHAT??”, “Umm, six mole, sir.” Variables do not have units. Thus while you cannot calculate the sum of “cat” and 5.3, a computer has no problem calculating the sum of six mole and three days.

Complex Types

Exercise: What variable type would you use for that photo you took last week of that western blot?

It is clear that these basic types don’t suffice. This touches on the topic of computer representation. How does a computer keep a western blot in memory? That photo you tool with your Android digitized the western blot into a matrix of numbers: if it was a greyscale photo, then a single integer per position.

Programming languages have various complex types, though most even support the definition of even

more complicated data structures. But the more basic complex types first: list. A list, vector,

or array all refer to the same concept: a list of variables, typically of the same type. For

example, a mathematical vector is a list of floats (e.g. float[] in JavaScript, where the

[] refers to the list or array nature). A string, actually, which we marked as a “basic”

variable type, is really a complex one too: it is a list of characters. That is, the string “cat”

is a list of three characters. Importantly, each item in the list has an index, and the full list

has a length. Depending on the programming language, the first item in the list has index 0 or 1.

As said, a list typically contains variables of the same type, just because it is easier to work

with. But the list can contain complex types too. For example, we can create a list of lists (we

would write float[][]). Each element in the top list is a list again; that is, the first

element of the outer list is again a list. This matches vary closes the mathematical matrix.

A second complex type important in this course is the map. A map is basically a list of key-value pairs, where they keys take the role of the index in lists. Instead of asking for the list item with index 7, we ask for the value behind a certain key. And, like we could make a list of lists, we can also make a map of maps, etc. Keep this in mind! We will use this extensively in this course.

Automation

Now that we know how the CPU uses memory, we turn back to what the processor must do, according to our program. First, I mentioned the step by step at the start. This is critical: the processor has a linear progression through the steps it must do. I can only go forward, and only step by step. It cannot go back. Yet, that is exactly what we write in a for-loop, like in this four line JavaScript example:

var sum = 0;

for (var i=1; i<50; i=1+1) {

sum = sum + i;

}

This code defines the variable sum in the first line, and then starts counting, from 1 to 50, one by one, and adding that number to the sum. This loop is only for our convenience. This is how the computer will run this program (and at a CPU machine instruction level it’s even longer):

var sum = 0;

var i=1;

sum = sum + i;

i=i+1;

sum = sum + i;

i=i+1;

sum = sum + i;

i=i+1;

sum = sum + i;

i=i+1;

sum = sum + i;

i=i+1;

sum = sum + i;

i=i+1;

sum = sum + i;

i=i+1;

sum = sum + i;

// ...

OK, I won’t give the full sequence of steps the computer takes. I guess you can see the virtues of higher level programming languages :) Importantly, it is a linear list of steps it takes.

Another important control structures in programming languages is the if-statement. This gives us the power of making decisions. For example, we can skip the 7 in the above summation:

var sum = 0;

for (var i=1; i<50; i=1+1) {

if (i == 7) {

} else {

sum = sum + i;

}

}

But I yet did not discuss another important concept: the operator. The operator tells the

computer what operation to perform, and how. This last source code example uses various operators: =, <, +, and ==. The first is an assignment operator: it assigns the value ‘0’

to the variable sum. This operation does not return anything. The < operator compares two

variable values, or a variable value with a specific value. For example, the above code compares

the value behind the ‘i’ variable with 50; indeed, it does not compare 50 with “i”, which is the

variable name. The + operator follows the mathematical + operator for floats and integers; for

strings the + operator performs a concatenation: "cat" + "fish" is not one less fish, but a

"catfish". Note that these two operators, < and +, return a new value. The < returns a

boolean (yes, it’s smaller; no, it’s not smaller); the + returns an integer if it was summing

integers, or a string when it concatenated two strings. The == operator also returns a boolean:

true of the two variables are the same (in general). During the course, we will see several more

operators. Look out for them!

In some way, this brings us to the next topic: functions of parameters. An operator is a special kind of function, and that will become more clear if I give an example function:

function add(first, second) {

var sum = first + second;

return sum;

}

Effectively, we just made an alias function “add” which internally just uses the + operator, with the exact same outcome.

Exercise: what would be returned by these two function calls? 1. add(1,2); 2. add(“cat”, “fish”);

This function example is not so interesting, and only makes the code harder to read. However,

when the “body” of the function becomes larger, it allows you to easily replace a complex list

of steps with one function call. Consider: sumAllNumbers(1,50).

Now, if we collect many such functions, pretty much like books, we get a library. So, that one was easy.

That includes this episode of the Programming in the Life Sciences series. I will continue later with the theory about Web Services and Clients, Serialization formats, and Other.